Rupee Under Pressure as FPIs Rush to the Exit Door

Context:

Since October last year, the continuous sell-off by foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) has resulted in a withdrawal of approximately Rs 2,00,000 crore from the domestic stock markets. The Russia-Ukraine war has heightened FPIs’ concerns, which are already anticipating interest rate hikes from the US Federal Reserve. Despite strong RBI intervention, the rupee has been hurt by the FPI withdrawal, with its exchange rate versus the dollar sliding below 76 to 76.16.

Relevance:

GS III- Indian Economy

Dimensions of the Article:

- Prospects in the near future

- Factors responsible for the pressure on rupee

- How is India bracing up?

- What is FPI?

- What are the categories of FPIs?

Prospects in the near future

Analysts believe the rupee would cross the 77 level against the dollar in the coming days if the situation in Ukraine worsens and FPI sales continue.

- Although banks have been buying dollars to ease FPI withdrawals, the RBI has been selling dollars from its forex reserves to save the rupee.

- This is likely to impact the IPO market and LIC’s plan for listing this fiscal and push up the current account deficit (CAD).

Factors responsible for the pressure on rupee

Three channels are harming the Indian rupee, bonds, and stocks as a result of the Russia-Ukraine conflict:

- Oil prices

- The US dollar index

- Global share prices

Analysts believe that if things worsen in Europe or if a new front opens up in Asia, there might be another transitory shock.

How is India bracing up?

- While the rupee is likely to stay under pressure, the RBI’s $631 billion forex fund will be sufficient to keep the currency from falling too far.

- Even the domestic institutional investors (DIIs), led by LIC, mutual funds and insurance companies, have been stepping up their purchases, absorbing most of the FPI sales.

What is FPI?

The FPI system, which is regulated by SEBI, provides a conduit for foreign investment in India. The Foreign Institutional Investor (‘FII’) and Qualified Foreign Investor (‘QFI’) regimes were merged into the FPI regime as a standardised path for foreign investment in India.

Regulations

- Permitted Instruments: Shares of listed Indian companies, non-convertible debt, units of domestic mutual funds, government securities, derivatives.

- A single FPI’s investment must be less than 10% of the Indian investee company’s post-issue paid-up share capital, and a collective investment must be less than 24%.

- An FPI’s (including linked FPIs) investment in a corporate bond issue must be less than 50%.

- Minimum residual maturity of more than one year for corporate bonds, subject to the condition that short-term corporate bond investments (less than one year residual maturity) do not exceed 20% of that FPI’s total corporate bond investment.

What are the categories of FPIs?

Cat I: Government and government related foreign investors such as Central Banks, Sovereign Wealth Funds.

Cat II: Funds, which are broad based and (i) appropriately regulated, or (ii) whose investment manager is appropriately regulated. Includes mutual funds (‘MF’), investment trusts, insurance / reinsurance companies. Also includes banks, Asset Management Companies, investment managers / advisors, portfolio managers, broker dealers and swap dealers, University funds, and Pension funds.

Cat III: Endowments, Charitable societies, Corporate bodies, Trusts, Family offices, Individuals**

** Non-resident Indians (NRIs) are not permitted to register as FPIs, however they can invest in FPIs, subject to conditions

Will Soaring Oil Prices Cause ‘Stagflation’ in India?

Context:

Crude oil prices have reached $140 per barrel. While oil prices have been progressively rising — they were less than $70 per barrel in December 2021— the most immediate cause of the increase is the possibility that the US may impose a ban on the purchase of Russian oil in retaliation to the invasion of Ukraine. Russia is the world’s second-largest oil producer, and if its oil is kept out of the market due to sanctions, prices would not only spike, but will also stay that way for a long time.

Relevance:

GS III- Indian Economy

Dimensions of the Article:

- Impact on India

- What will happen to inflation?

- Estimates were not encouraging either

- What is Stagflation?

- Recent instances in India

- Risk of stagflation

Impact on India

Although India is not directly involved in the conflict, it will be negatively impacted if oil prices continue to rise.

- More than 84 percent of India’s entire oil needs is imported.

- India’s economy would grind to a standstill without these imports, both symbolically and literally.

- Indian consumers have been insulated from the spike in petrol costs since December due to the compulsions of electoral politics following the Assembly elections.

- The most recent increases could indicate a major increase in domestic oil prices, assuming that the governments — both federal and state — do not cut taxes. Higher oil prices will raise inflation and the general price level even more.

What will happen to inflation?

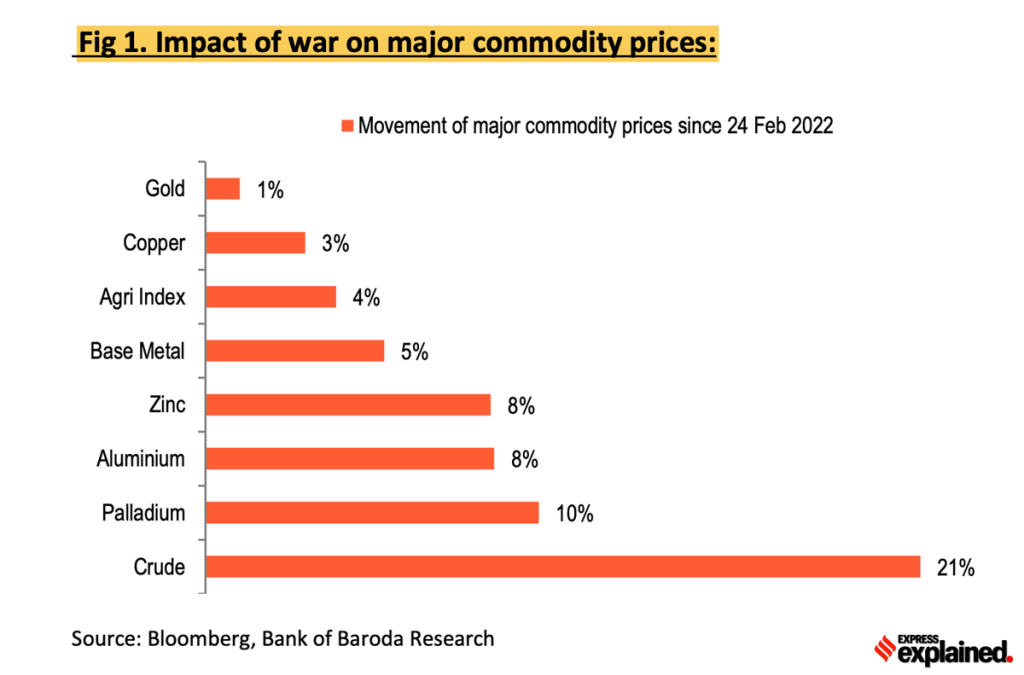

A 10% increase in crude oil prices results in a 9% increase in wholesale inflation and a 5% increase in retail inflation. To put things in perspective, between February 24 and March 3, crude oil prices increased by more than 20%.

- Increased inflation would deprive Indians of their purchasing power, lowering overall demand. The sluggish consumer demand is the largest problem in India’s GDP growth story. India’s largest growth engine is private consumer demand. The monetary sum of household personal purchases makes for more than 55 percent of India’s overall GDP.

- Increased prices will limit demand, which is already battling to return to pre-Covid levels. As a result of fewer goods and services being demanded, businesses will be less likely to invest in new capacity, which would, in turn, reduce demand turn, will exacerbate the unemployment crisis and lead to even lower incomes.

Estimates were not encouraging either

Even before the Ukraine crisis, India’s GDP growth had begun to show symptoms of slowing.

- The economy grew by only 5.4 percent in Q3 (October to December) GDP statistics, indicating that the economy grew by only 5.4 percent in a period that usually sees a boost due to higher demand due to multiple festivals (such as Diwali).

- Furthermore, Covid instances were at their lowest point in the quarter. A growth rate of less than 6% did not bode well. Particularly because Q4 (which is currently underway) is expected to be significantly poorer — both as a result of the Omicron impact and the ongoing Ukraine situation.

Analysts have been downgrading their growth and inflation estimates for India, which is unsurprising. These are some of the milder effects. One major concern is that such a significant increase in oil costs could force a relatively weak country like India into stagflation.

What is Stagflation?

Stagflation is a term that combines slow growth and rising inflation.

- In most cases, growing inflation occurs when an economy is booming: people are earning a lot of money, demanding a lot of products and services, and prices continue to rise as a result. Prices tend to stall when demand is low and the economy is in the doldrums, according to the contrary reasoning (or even fall).

- Stagflation, on the other hand, is a scenario in which an economy has the worst of both worlds: growth is mainly stagnate (along with rising unemployment), and inflation is not only high, but consistently so.

Why does this unusual thing happen?

The most well-known instance of stagflation occurred in the early and mid-1970s. The OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) had resolved to reduce crude oil supply. Oil prices shot up by about 70% around the world as a result of this.

- This unexpected increase in oil prices not only increased inflation worldwide, particularly in Western economies, but also hampered their ability to produce, stifling their economic progress. Stagflation was caused by high inflation and stopped growth (along with the consequent unemployment).

Recent instances in India

This subject has gotten a lot of attention recently, especially since late 2019, when retail inflation soared due to unseasonal rainfall, which caused a spike in food inflation.

- In December 2019, the administration found it increasingly difficult to deny that India’s growth rate was slowing over time. India’s GDP growth rate had slowed from over 8% in 2016-17 to just 3.7 percent in 2019-20.

- However, the government denied ‘stagflation’ on the grounds that India’s GDP was still increasing in absolute terms, albeit at a slower pace. The government was confident at the time that things will improve after a lull of 2-3 years. Also high inflation at the time was seen to be transitory — only caused by unseasonal rains. Stagflation requires inflation to be not just high but also persistent over a long period.

- Then, in late 2020, this subject arose again, because by October of that year, it had become evident that India’s GDP would decrease as a result of the Covid epidemic. India had entered what is known as a technical recession. The fact that inflation had not abated only made problems worse. On the contrary, everyone, including the RBI, was taken aback by the price increase that persisted despite significant demand destruction.

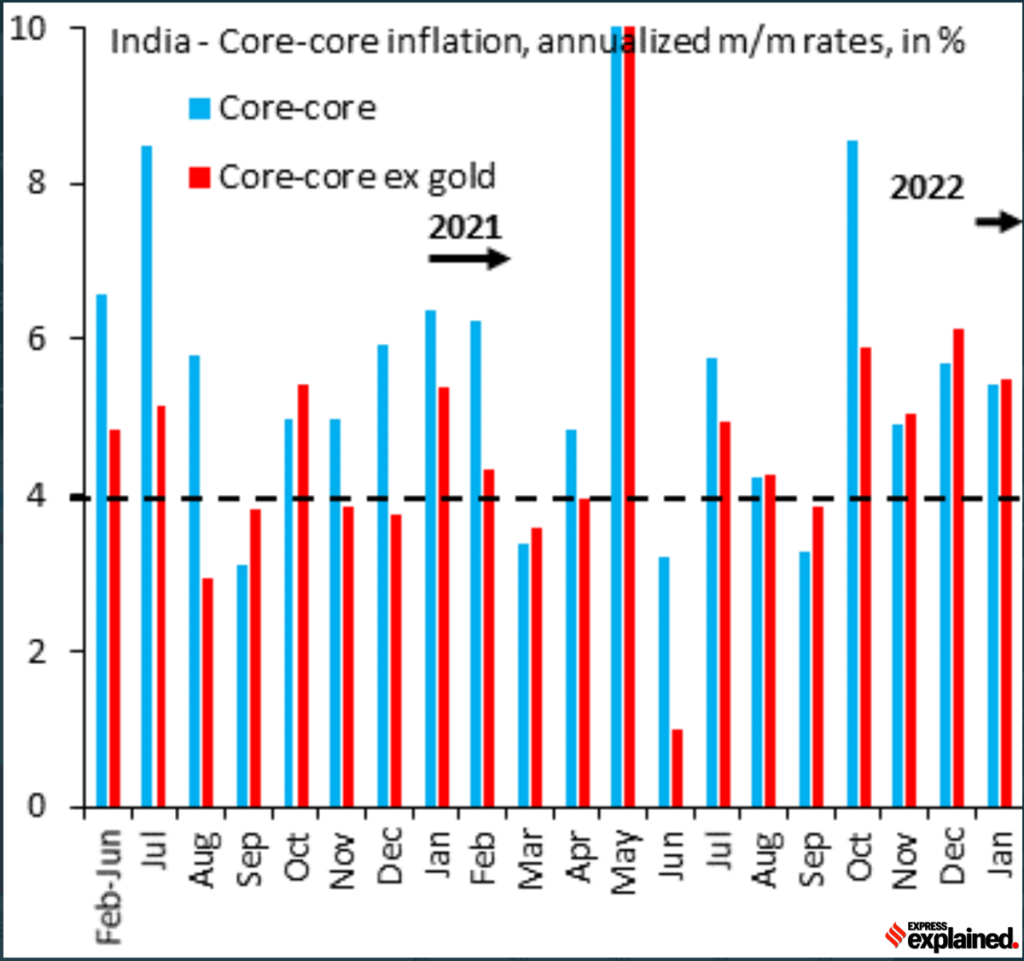

- Since December 2021, numerous prominent voices have claimed that India is experiencing stagflation. In FY23, there is a growing consensus about a significant gap in output compared to pre-covid pre-shadow banking crisis trend output. Despite this, core inflation is running at above 5% net of base effects. The RBI’s ultra-dovish stance appears to be a source of concern.

Even core inflation, which typically removes the effect of food price spikes and fuel price spikes, has been persistently high in comparison to the RBI’s target of 4% for the headline (which includes the higher fuel and food prices) retail inflation.

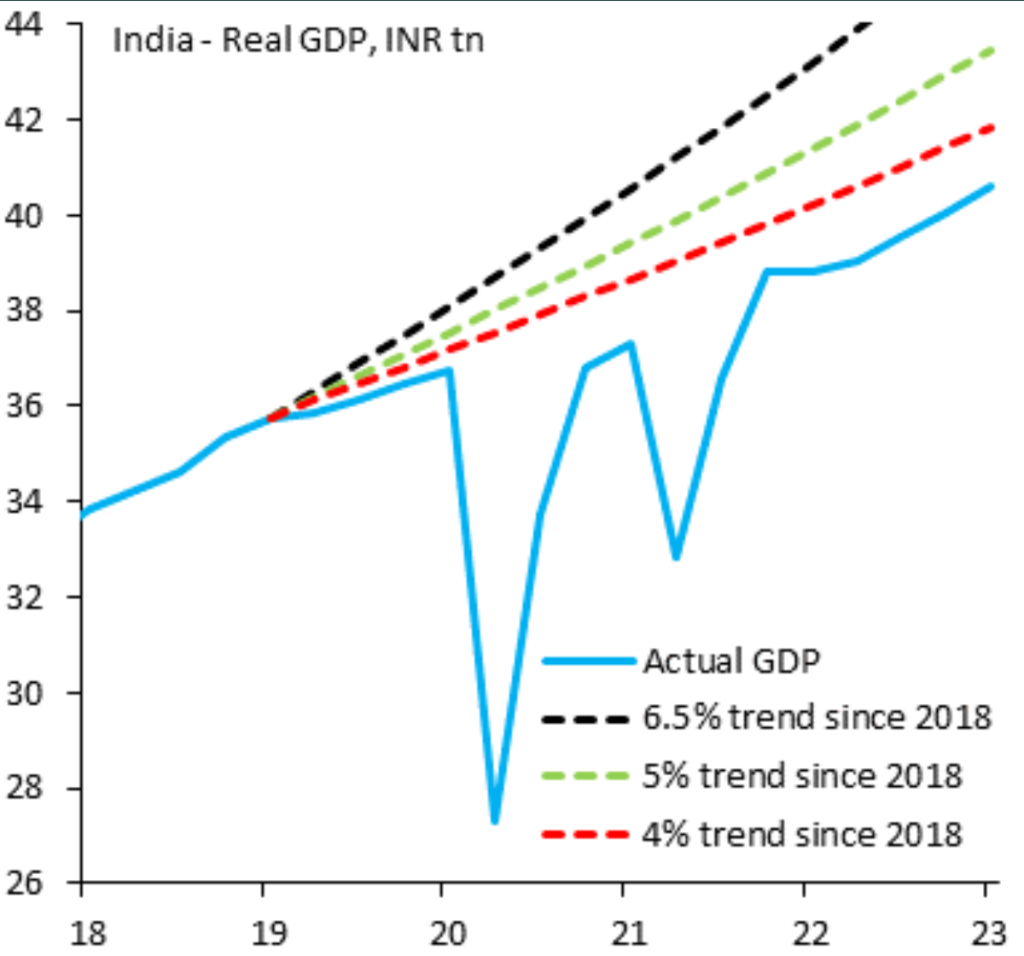

Since 2018, India’s actual GDP (blue line) is on a trajectory that pales in comparison to even a 4% GDP growth rate — infamously referred to as the Hindu Rate of Growth.

Why others do not believe that stagflation exists?

The Covid outage was a jolt to India’s economy’s trend growth. Because all of the factors are measured with relation to a particular trend, the entire hypothesis (of stagflation) is based on the economy failing to achieve the trend. So how can one talk about stagflation if the trend growth rate has shifted as a result of Covid.

Risk of stagflation

If oil prices remain high for an extended period of time, the inflation situation will deteriorate significantly. Crude oil prices could reach $185 by the end of the year, according to some sources. Even if they do not rise to that level, average costs will likely remain above $100. Because oil is such a basic cost in our economy, this increase will almost certainly result in substantial inflation for Indians, especially because it comes after two years of already higher prices and lower incomes.

The other criterion is that growth must come to a halt. The unemployment rate (or, in India’s case, the employment rate) is a good indicator of whether present growth levels are adequate. India is experiencing the worst unemployment crisis it has faced in the last five decades, according to government figures. Any broad-based recovery in demand will almost certainly be hampered by high inflation.

So, as implausible as it may seem, if crude oil continues to rise and stay high for an extended period of time as India’s GDP growth slows, we may be in for a shock and would be looking at stagflation in the near future.

Democracy Report 2022

Context:

According to the latest report from the V-Dem Institute at Sweden’s University of Gothenburg, the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2021 is down to 1989 levels, with the democratic gains of the post-Cold War period eroding rapidly in the last few years.

- The study, titled ‘Democracy Report 2022: Autocratisation Changing Nature?’

Relevance:

GS II- Polity & Constitution, International Relations

Dimensions of the Article:

- V-Dem report’s methodology

- Parameters to assess the status of a democracy

- Main findings of the report

- What does the report say about the changing nature of autocratisation?

V-Dem report’s methodology

- Since key features of democracy, such as, judicial independence, are not directly measurable, and to rule out distortions due to subjective judgments, V-Dem uses aggregate expert judgments to produce estimates of critical concepts.

- It gathers data from a pool of over 3,700 country experts who provide judgments on different concepts and cases.

- Leveraging the diverse opinions, the V-Dem’s measurement model algorithmically estimates both the degree to which an expert is reliable relative to other experts, and the degree to which their perception differs from other experts to come up with the most accurate values for every parameter.

Parameters to assess the status of a democracy

V-Dem’s conceptual scheme takes into account not only the electoral dimension (free and fair elections) but also the liberal principle that a democracy must protect “individual and minority rights against both the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority”.

The V-Dem report classifies countries into four regime types based on their score in the Liberal Democratic Index (LDI):

- Liberal Democracy,

- Electoral Democracy,

- Electoral Autocracy,

- Closed Autocracy.

Liberal Democratic Index (LDI):

The LDI captures both liberal and electoral aspects of a democracy based on 71 indicators that make up the Liberal Component Index (LCI) and the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI).

- Liberal Component Index (LCI): The LCI measures aspects such as protection of individual liberties and legislative constraints on the executive,

- Electoral Democracy Index (EDI): It considers indicators that guarantee free and fair elections such as freedom of expression and freedom of association.

In addition, the LDI also uses an

- Egalitarian Component Index: to what extent different social groups are equal,

- Participatory Component Index: health of citizen groups, civil society organisations,

- Deliberative Component Index: whether political decisions are taken through public reasoning focused on common good or through emotional appeals, solidarity attachments, coercion.

Main findings of the report

- While Sweden topped the LDI index, other Scandinavian countries such as Denmark and Norway, along with Costa Rica and New Zealand make up the top five in liberal democracy rankings.

- Autocratisation is spreading rapidly, with a record of 33 countries autocratising.

- Signaling a sharp break from an average of 1.2 coups per year, 2021 saw a record 6 coups, resulting in 4 new autocracies: Chad, Guinea, Mali and Myanmar.

- While the number of liberal democracies stood at 42 in 2012, their number has shrunk to their lowest level in over 25 years, with just 34 countries and 13% of the world population living in liberal democracies.

- Closed autocracies, or dictatorships, rose from 25 to 30 between 2020 and 2021.

- While the world today has 89 democracies and 90 autocracies, electoral autocracy remains the most common regime type, accounting for 60 countries and 44% of the world population or 3.4 billion people.

- Electoral democracies were the second most common regime, accounting for 55 countries and 16% of the world population.

India:

- The report notes that India is part of a broader global trend of an anti-plural political party driving a country’s autocratisation.

- Ranked 93rd in the LDI, India figures in the “bottom 50%” of countries.

- It has slipped further down in the Electoral Democracy Index, to 100, and even lower in the Deliberative Component Index, at 102.

- In South Asia, India is ranked below Sri Lanka (88), Nepal (71), and Bhutan (65) and above Pakistan (117) in the LDI.

What does the report say about the changing nature of autocratisation?

- Toxic polarisation: One of the biggest drivers of autocratisation is “toxic polarisation” — defined as a phenomenon that erodes respect of counter-arguments and associated aspects of the deliberative component of democracy — a dominant trend in 40 countries, as opposed to 5 countries that showed rising polarisation in 2011.

- The report also points out that “toxic levels of polarisation contribute to electoral victories of anti-pluralist leaders and the empowerment of their autocratic agendas”.

- Noting that “polarisation and autocratisation are mutually reinforcing”, the report states that “measures of polarisation of society, political polarisation, and political parties’ use of hate speech tend to systematically rise together to extreme levels.”

- Misinformation: The report identified “misinformation” as a key tool deployed by autocratising governments to sharpen polarisation and shape domestic and international opinion.

- Repression of civil society and censorship of media were other favoured tools of autocratising regimes.

- While freedom of expression declined in a record 35 countries in 2021, with only 10 showing improvement, repression of civil society organisations (CSOs) worsened in 44 countries over the past ten years, “putting it at the very top of the indicators affected by autocratisation”.

- Significantly, the report also found that decisive autonomy for the electoral management body (EMB) deteriorated in 25 countries.

-Source: The Hindu

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

Context:

The global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has retained Pakistan on its terrorism financing “grey list”.

Relevance:

GS-II: International Relations (International Groupings or Agreements affecting India’s Interests, India’s neighbors), GS-III: Internal Security Challenges (Terrorism in Hinterland & Border Areas)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

- FATF Greylists

- FATF Blacklists

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

- The Financial Action Task Force (on Money Laundering) (FATF) is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1989 on the initiative of the G7 to develop policies to combat money laundering.

- In 2001, its mandate was expanded to include terrorism financing.

- FATF is a “policy-making body” that works to generate the necessary political will to bring about national legislative and regulatory reforms in these areas.

- FATF monitors progress in implementing its Recommendations through “peer reviews” (“mutual evaluations”) of member countries.

- Since 2000, FATF has maintained the FATF blacklist (formally called the “Call for action”) and the FATF greylist (formally called the “Other monitored jurisdictions”).

- The objectives of FATF are to set standards and promote effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combating money laundering, terrorist financing and other related threats to the integrity of the international financial system.

FATF Greylists

- FATF greylist is officially referred to as Jurisdictions Under Increased Monitoring.

- FATF grey list represent a much higher risk of money laundering and terrorism financing but have formally committed to working with the FATF to develop action plans that will address their AML/CFT deficiencies.

- The countries on the grey list are subject to increased monitoring by the FATF, which either assesses them directly or uses FATF-style regional bodies (FSRBs) to report on the progress they are making towards their AML/CFT goals.

- While grey-list classification is not as negative as the blacklist, countries on the list may still face economic sanctions from institutions like the IMF and the World Bank and experience adverse effects on trade.

- Unlike the next level “blacklist”, greylisting carries no legal sanctions, but it attracts economic strictures and restricts a country’s access to international loans

FATF Blacklists

- FATF Blacklists is Officially known as High-Risk Jurisdictions subject to a Call for Action.

- FATF blacklist sets out the countries that are considered deficient in their anti-money laundering and counter-financing of terrorism regulatory regimes.

- The list is intended to serve not only as a way of negatively highlighting these countries on the world stage, but as a warning of the high money laundering and terror financing risk that they present.

- It is extremely likely that blacklisted countries will be subject to economic sanctions and other prohibitive measures by FATF member states and other international organizations.

Effects of FATF Blacklisting

- The effect of the FATF Blacklist has been significant, and arguably has proven more important in international efforts against money laundering than has the FATF Recommendations.

- While, under international law, the FATF Blacklist carried with it no formal sanction, in reality, a jurisdiction placed on the FATF Blacklist often found itself under intense financial pressure.

- FATF makes sure funds are not easily accessible by terror organisations that are causing crimes against humanity.

- FATF has helped to fight against corruption by ‘grey-listing’ countries that do not meet Recommended Criteria and this helps to cripple economies and states that are aiding terrorist and corrupted organisations.

Tiger Density of India

Context:

Preliminary findings of a study by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) suggest that the density of tigers in the Sunderbans may have reached the carrying capacity of the mangrove forests, leading to frequent dispersals and a surge in human-wildlife conflict.

Relevance:

GS II- Environment and Ecology

Dimensions of the Article:

- Tiger density of India

- Conflict: cause or effect

- The way ahead

Tiger density of India

- In the Terai and Shivalik hills habitat — think Corbett tiger reserve, for example — 10-16 tigers can survive in 100 sq km.

- This slides to 7-11 tigers per 100 sq km in the reserves of north-central Western Ghats such as Bandipur, and to 6-10 tigers per 100 sq km in the dry deciduous forests, such as Kanha, of central India.

- The correlation between prey availability and tiger density is fairly established.

- There is even a simple linear regression explaining the relationship in the 2018 All-India Tiger report that put the carrying capacity in the Sunderbans “at around 4 tigers” per 100 sq km.

- A joint Indo-Bangla study in 2015 pegged the tiger density at 2.85 per 100 sq km after surveying eight blocks spanning 2,913 sq km across the international borders in the Sunderbans.

Conflict: cause or effect

- The consequence, as classical theories go, is frequent dispersal of tigers leading to higher levels of human-wildlife conflict in the reserve peripheries.

- Physical (space) and biological (forest productivity) factors have an obvious influence on a reserve’s carrying capacity of tigers, what also plays a crucial role is how the dispersal of wildlife is tolerated by people — from the locals who live around them to policymakers who decide management strategies.

- While this not-so-discussed social carrying capacity assumes wider significance for wildlife living outside protected forests, it is an equally important factor in human-dominated areas bordering reserves where periodic human-wildlife interface is inevitable.

- More so when different land uses overlap and a good number of people depend on forest resources for livelihood.

The way ahead

- Artificially boosting the prey base in a reserve is often an intuitive solution but it can be counter-productive. While tackling external factors, such as bushmeat hunting, is necessary to ease pressure on the tiger, the government’s policies have discouraged reserve managers from striving to increase tiger densities by artificial management practices of habitat manipulation or prey augmentation.

- To harness the umbrella effect of tigers for biodiversity conservation, experts say, it is more beneficial to increase areas occupied by tigers.

- For many, the prescription is to create safe connectivity among forests and allow tigers to disperse safely to new areas. But though vital for genes to travel and avoid a population bottleneck, wildlife corridors may not be the one-stop solution for conflict.

- First, not all dispersing tigers will chance upon corridors simply because many will find territories of other tigers between them and such openings.

- Even the lucky few that may take those routes are likely to wander to the forest edges along the way.

- Worse, the corridors may not lead to viable forests in reserves such as Sunderbans, bounded by the sea and villages.