Supreme Court on Free Speech on Social Media: Navigating the Digital Wild West

Syllabus: GS2/ Indian Constitution (Fundamental Rights); Governance (Social Media Regulation, Judiciary)

In Context

The Supreme Court of India has recently been grappling with the complex and evolving landscape of free speech on social media. In a series of observations and hearings in July 2025, the apex court has expressed deep concern over the “abuse” of fundamental rights on digital platforms, particularly regarding the spread of divisive, offensive, and even derogatory content. These discussions highlight the judiciary’s attempt to strike a delicate balance between upholding the cherished right to freedom of speech and expression and addressing the detrimental consequences of its misuse in the online realm.

Constitutional Framework: Article 19(1)(a) and its Limitations

- Article 19(1)(a): The bedrock of free speech in India, it guarantees to all citizens the “right to freedom of speech and expression.” This right is expansive and includes the freedom to express one’s views and opinions through various mediums, including print, electronic, and now, increasingly, social media.

- Article 19(2): Crucially, Article 19(1)(a) is not absolute. Article 19(2) allows the State to impose “reasonable restrictions” on this right in the interests of:

- Sovereignty and integrity of India

- Security of the State

- Friendly relations with foreign states

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Contempt of court

- Defamation

- Incitement to an offense

Recent Supreme Court Observations and Cases (July 2025)

Several benches of the Supreme Court have recently weighed in on the issue, signaling a renewed judicial focus on social media conduct:

- Emphasis on Self-Regulation (Wazahat Khan Case):

- A bench of Justices B.V. Nagarathna and K.V. Viswanathan, while hearing a plea by Wazahat Khan (facing multiple FIRs for controversial posts targeting a Hindu deity), stressed that citizens must “know the value of the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression” and practice “self-restraint” and “self-regulation.”

- Justice Nagarathna remarked that “abuse of that freedom” was “clogging the courts” and warned that if citizens do not regulate themselves, the State might have to intervene, something “nobody wants.”

- The Court clarified that its approach was not about censorship but about fostering “fraternity among citizens” and curbing “divisive tendencies” on social media. It also reiterated that the reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2) are “rightly been placed.”

- Dignity over Unfettered Speech (Samay Raina and Others Case):

- Another bench of Justices Surya Kant and Joymalya Bagchi heard a case against social media influencers (including Samay Raina) accused of ridiculing people with disabilities.

- Justice Kant sternly observed that such conduct was “damaging” and “demoralising,” necessitating “serious remedial and punitive action.”

- He emphasized that the “right to dignity also emanates from the right which someone else is claiming” and highlighted that Article 19 (free speech) “can’t overpower Article 21 (right to life and dignity).” In the event of a conflict, Article 21 “has to trump Article 19.”

- The Court also asked the Attorney General to assist in framing guidelines that balance freedom of speech with the rights and dignity of others, stressing the need for these guidelines to be in conformity with constitutional principles.

- “Abuse” of Freedom and Offensive Content (Hemant Malviya Case):

- A bench of Justices Sudhanshu Dhulia and Aravind Kumar, while hearing an anticipatory bail plea by cartoonist Hemant Malviya (booked for objectionable posts about the Prime Minister and RSS workers), questioned, “Why do you do all this?”

- Justice Dhulia remarked that “this is definitely the case that the freedom of speech and expression is being abused,” pointing to the “highly offensive language” often found in social media content.

- Centre’s Stance on “Unlawful Content” and “Safe Harbour” (X Corp Case):

- In a separate but related hearing before the Karnataka High Court, the Centre (through the Solicitor General) argued that allowing the proliferation of “unlawful content” on social media in the name of free speech “endangered democracy.”

- The government accused X (formerly Twitter) of attempting to evade accountability by taking shelter under the IT Act’s “safe harbour” protection. The Centre argued that “safe harbour” is a statutory privilege, not an unconditional entitlement, contingent upon platforms promptly removing unlawful content.

- The government even demonstrated the ease of creating a fake verified account of the “Supreme Court of Karnataka” to highlight the potential for misinformation and impersonation, stating that social media platforms’ algorithms “actively curate and boost content, shaping public opinion,” which demands “heightened accountability.”

Previous Landmark Rulings and Ongoing Challenges

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015): This landmark judgment struck down Section 66A of the IT Act, which allowed arrests for “offensive” online posts, ruling it unconstitutional for violating freedom of speech. The court emphasized the importance of free speech in a democracy and the need for strict interpretation of restrictions. This case remains a cornerstone of free speech jurisprudence in the digital age.

- Recent Trends (Post-Shreya Singhal): Despite Shreya Singhal, challenges persist. There has been a rise in FIRs over controversial social media content, leading to concerns about a “chilling effect” on free expression. The Supreme Court has also had to intervene in cases where individuals face multiple FIRs across states for similar online content, often granting interim protection.

- “Horizontal Application” of Rights: The Supreme Court, in some recent verdicts, has recognized a “horizontal approach” to free speech, meaning citizens can invoke the right not just against the state but also against other citizens, implying that one citizen’s speech cannot violate another’s fundamental rights (like dignity).

The Delicate Balance and Way Forward

The Supreme Court’s latest interventions underscore the difficulty in regulating social media content in a manner that respects fundamental rights while combating its negative externalities. The path forward involves:

- Promoting Digital Literacy and Self-Regulation: Empowering citizens with digital literacy to critically evaluate online content and fostering a sense of civic responsibility for their online conduct. The Court’s emphasis on self-restraint is a step in this direction.

- Clearer Legal Frameworks: The government, in consultation with legal experts and stakeholders, needs to develop a robust and constitutionally compliant regulatory framework for social media, addressing issues like hate speech, misinformation, and content moderation, without resorting to over-censorship. The Attorney General’s assistance in framing guidelines is crucial.

- Accountability of Intermediaries: Defining the responsibilities of social media platforms (intermediaries) more clearly, ensuring they exercise due diligence and swiftly act against unlawful content without becoming arbiters of free speech.

- Expeditious Judicial Process: Fast-tracking cases related to online content to ensure timely justice for victims of abuse and to deter misuse, without stifling legitimate expression.

- Differentiating “Offensive” from “Unlawful”: Courts must consistently apply the tests of “reasonable restrictions” under Article 19(2) and distinguish between content that may be offensive or in “poor taste” but is not unlawful, and content that genuinely constitutes a criminal offense (e.g., incitement to violence, defamation, or hate speech).

The Supreme Court’s current stance reflects a concern that while free speech is vital for democracy, its “abuse” on social media can undermine societal harmony and clog the justice system. The ongoing debates and evolving jurisprudence are critical in shaping the future of digital free speech in India, balancing individual liberty with collective responsibility and public order.

Union Government Report on Protection of Civil Rights Act (PCR Act) 1955: A Critical Review of Implementation

Syllabus: GS2/ Polity and Governance (Vulnerable Sections, Government Policies and Interventions); Social Justice

In Context

The Union government’s 2022 annual report on the implementation of the Protection of Civil Rights Act (PCR Act) 1955, made public by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, sheds light on the persistent challenges in combating “untouchability” and enforcing civil rights in India. The report reveals a concerning trend of low case registration, high pendency, and dismal conviction rates, indicating significant gaps in the Act’s effective implementation despite its constitutional mandate.

Background of the Protection of Civil Rights Act (PCR Act) 1955

- Constitutional Basis: The PCR Act draws its strength from Article 17 of the Indian Constitution, which unequivocally abolishes “Untouchability” and forbids its practice in any form. It further states that the enforcement of any disability arising out of “Untouchability” shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law. This makes untouchability a legally prohibited act since the Constitution came into force on January 26, 1950.

- Evolution: To operationalize Article 17, the Parliament enacted the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955, on May 8, 1955. This Act was a direct response to the constitutional mandate to criminalize acts of discrimination based on untouchability.

- Renaming and Broadening Scope: In 1976, the Act was comprehensively amended and renamed as the “Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955.” This amendment broadened its scope, shifting the focus from merely “offences” to the “protection of civil rights” arising from the abolition of untouchability. The Protection of Civil Rights Rules were notified in 1977.

Key Provisions of the PCR Act 1955

The Act defines “Civil Rights” as “any right accruing to a person by reason of the abolition of untouchability under Article 17 of the Constitution.” It prescribes punishments for various offenses committed on the ground of “untouchability,” including:

- Sections 3-7A (Offences and Punishments):

- Preventing any person from entering public places of worship or using sacred water resources (Section 3).

- Denial of access to shops, public restaurants, hotels, public entertainment venues, cremation grounds, etc. (Section 4).

- Refusal of admission to hospitals, dispensaries, educational institutions, or hostels (Section 5).

- Refusal to sell goods or render services (Section 6).

- Punishment for other offenses arising out of “untouchability,” such as molestation, causing injury, insult, refusal to occupy a house/land, or practice any trade/business (Section 7).

- Declaring unlawful compulsory labor as a practice of “untouchability” (Section 7A).

- Sections 8-11 (Preventive/Deterrent Provisions):

- Cancellation or suspension of licenses upon conviction (Section 8).

- Resumption or suspension of grants made by the Government (Section 9).

- Punishment for willful neglect of investigation by a public servant (Section 10).

- Power of State Government to impose collective fine (Section 10A).

- Enhanced penalty on subsequent conviction (Section 11).

- Other Provisions:

- All offenses under the Act are cognizable and non-compoundable.

- Section 12 creates a legal presumption that if an offense under the Act is committed against a member of a Scheduled Caste, the court shall presume it was committed on the ground of untouchability.

- Section 15A places a duty on both Central and State Governments to ensure effective implementation, including providing legal aid, appointing officers, setting up special courts, and identifying “untouchability-prone” areas.

- The Central Government is mandated to place an annual report on the measures taken by itself and the State Governments before each House of Parliament (Section 15A(4)).

Challenges Highlighted by the 2022 Report

The Union government’s 2022 report brings to the fore several critical challenges impeding the Act’s effectiveness:

- Underreporting and Declining Case Registration:

- The report indicates a very low number of cases registered under the PCR Act. For instance, only 13 cases were registered nationwide under the PCR Act in 2022, a decline from 24 in 2021 and 25 in 2020.

- This low figure does not necessarily signify a reduction in untouchability practices. Instead, it suggests widespread underreporting due to:

- Lack of awareness among victims about the Act’s provisions.

- Fear of retaliation or social boycott from dominant groups.

- Reluctance to engage with the formal legal system.

- Preference for registering cases under the more stringent Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (PoA Act), which has a broader scope and more punitive measures for caste-based atrocities.

- High Pendency and Poor Conviction Rates:

- The judicial processing of cases under the PCR Act remains sluggish. In 2022, 1,242 cases under the PCR Act were pending trial in courts.

- The pendency rate in courts remains alarmingly high, above 97%. This means a vast majority of cases filed are stuck in the judicial pipeline for years.

- Out of 31 cases disposed of in 2022, only 1 resulted in conviction, while 30 ended in acquittals. This abysmal conviction rate (around 3%) highlights severe gaps in investigation, evidence collection, prosecution, and witness protection.

- Ineffective Enforcement:

- The very high rates of acquittals and pendency signal systemic weaknesses in the enforcement machinery. This includes deficiencies in police investigation, collection of corroborative evidence, lack of witness and victim protection, and slow judicial processes.

- The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) compiles and publishes crime data, including cases under the PCR Act, but the consistent low numbers under this specific Act raise questions about its practical utility in addressing the daily manifestations of untouchability.

- Overlapping Legislation and Prioritization of PoA Act:

- The enactment of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (PoA Act), with its broader coverage of caste-based violence, discrimination, and specific provisions for victims’ compensation and rehabilitation, has effectively shifted the majority of caste-related crime prosecutions under its ambit.

- The PCR Act, while foundational, now often deals with less severe offenses or instances not explicitly covered by the PoA Act, leading to its diminished use in practice.

- Lack of State Initiative and Infrastructure:

- Despite the mandate under Section 15A, several States and Union Territories have reportedly not established the required infrastructure, such as special courts, vigilance and monitoring committees, or robust reporting systems.

- This non-compliance by some state governments undermines the intended purpose and effective implementation of the Act at the grassroots level.

Way Forward and Recommendations

For the PCR Act to truly fulfill its constitutional objective and become an effective tool against untouchability, comprehensive reforms and concerted efforts are required:

- Strengthen Enforcement Mechanisms:

- Revamp and strengthen investigative machinery: Police personnel need specialized training in handling cases under the PCR Act, focusing on meticulous evidence collection and prompt action.

- Enhance prosecution capabilities: Improve coordination between police and public prosecutors to build stronger cases and reduce acquittals.

- Ensure witness protection: Implement robust witness protection programs to prevent intimidation and ensure witnesses can testify freely.

- Improve Judicial Efficiency:

- Establish more Special Courts: Expedite the setting up of special courts mandated by the Act to fast-track trials and reduce pendency.

- Judicial sensitization: Regular training and sensitization programs for judges on the historical and social context of untouchability and the purpose of the Act.

- Increase Awareness and Legal Aid:

- Mass awareness campaigns: Launch extensive campaigns to educate Dalit communities about their rights under the PCR Act and the PoA Act, and how to access legal recourse.

- Strengthen legal aid: Provide adequate facilities and free legal aid to persons subjected to discrimination due to untouchability.

- Better Coordination and Monitoring:

- Improve data collection: Ensure more accurate and granular data collection on incidents of untouchability, regardless of whether a formal case is registered.

- Regular monitoring and reporting: States must consistently submit comprehensive annual reports and establish effective vigilance and monitoring committees at state and district levels.

- Identify “untouchability-prone” areas: Actively identify and declare such areas and implement specific measures to eliminate the practice.

- Synergy with PoA Act: Ensure better coordination and understanding between the implementation of the PCR Act and the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, to provide the most effective legal recourse for victims.

- Address Root Causes:

- Beyond legal measures, the government must continue to focus on educational and economic empowerment programs for Scheduled Castes to raise their living standards, build confidence, and challenge discriminatory social attitudes.

- Promote inter-caste harmony and eliminate caste-based biases in society through public education and social reforms.

The Union government’s report serves as a stark reminder that despite decades of legal prohibition, the practice of untouchability persists. True eradication requires not just strong laws, but robust enforcement, a responsive justice system, and a sustained societal commitment to equality and dignity for all.

10 Years of Skill India Mission: A Decade of Transformation and Future Ambitions

Syllabus: GS2/ Government Policies and Interventions; GS3/ Indian Economy (Employment, Skilling); Social Justice (Poverty Alleviation, Demographic Dividend)

In Context

July 15, 2025, marks the 10th anniversary of the Skill India Mission (SIM), a flagship initiative launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Coinciding with World Youth Skills Day, this milestone prompts a reflection on a decade of concerted efforts by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) to transform India’s workforce, empower its youth, and harness the nation’s demographic dividend. Union Minister Jayant Chaudhary recently launched a week-long celebration, dubbed ‘Kaushal ka Dashak’ (Decade of Skills), highlighting the Mission’s significant impact and outlining the roadmap for future skilling initiatives.

The Genesis and Objectives of Skill India Mission

Launched in July 2015, the Skill India Mission aimed to unify India’s fragmented skilling ecosystem and provide industry-relevant training, foster entrepreneurship, and promote global workforce mobility. The core objectives included:

- Bridging the Skill Gap: Addressing the mismatch between the skills possessed by the workforce and the demands of various industries.

- Enhancing Employability: Equipping youth with practical, market-oriented skills to increase their chances of securing quality employment.

- Promoting Entrepreneurship: Fostering an entrepreneurial culture by providing training, credit linkages, and market support.

- Standardization and Quality: Ensuring high-quality training aligned with national and international standards.

- Inclusivity: Extending skill development opportunities to all sections of society, including women, Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and those in rural and underserved areas.

- Demographic Dividend: Capitalizing on India’s young population (65% under 35) to boost economic growth and global competitiveness.

Key Achievements over the Decade (2015-2025)

Over the past decade, the Skill India Mission has made significant strides through various schemes and initiatives:

- Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY):

- The flagship short-term training program, PMKVY, has seen multiple phases (1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and currently 4.0).

- As of July 2025, over 1.63 crore youth have been trained under PMKVY across diverse sectors like manufacturing, healthcare, IT, and construction.

- PMKVY 4.0 (2022-25) is focusing on future skills, including AI, 5G, cybersecurity, green hydrogen, and drone technology, and integrates with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 through initiatives like the Academic Bank of Credits (ABC).

- National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS):

- PM-NAPS aims to boost apprenticeship training by providing financial support for stipends (now proposed to increase by 36% to enhance attractiveness).

- As of May 2025, over 43.47 lakh apprentices have been engaged across 36 States/UTs, involving over 51,000 establishments.

- A special pilot scheme offers an additional ₹1,500 per month to North Eastern Region (NER) candidates undergoing apprenticeship training to promote regional inclusivity.

- Jan Shikshan Sansthan (JSS) Scheme:

- A community-based vocational training program for non-literates, neo-literates, and school dropouts (aged 15–45), primarily in rural and low-income urban areas.

- Between FY 2018–19 and 2023–24, over 26 lakh individuals have been trained under JSS. It is integrated with initiatives like PM JANMAN and ULLAS for inclusive skilling.

- Institutional Strengthening:

- Over 14,500 Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) have been supported through reforms in quality, governance, and affiliation norms.

- A ₹60,000 crore ITI Revamp Scheme has been approved by the Cabinet (with ₹10,000 crore from CSR contributions) to make ITIs future-ready and align curriculum with industry needs.

- The de-affiliation of 4.5 lakh vacant ITI seats over the last six years and ongoing action on 99,000 more unutilized seats reflects a commitment to quality over mere numbers.

- Admission rates in ITIs increased by 11% in 2024, indicating renewed trust in the system.

- Two new Centres of Excellence (CoE) have been launched at National Skill Training Institutes (NSTIs) in Hyderabad and Chennai in 2025, focusing on advanced instructor training and skilling in AI, robotics, and green technologies.

- New Age Schemes and Initiatives:

- PM Vishwakarma Yojana (launched Sep 2023): Supports traditional artisans and craftspeople across 18 trades, providing toolkits, digital incentives, collateral-free credit, and market linkages. As of July 2025, over 29 lakh artisans have registered.

- Rural Self Employment and Training Institutes (RSETIs): Bank-led residential training centers for rural youth entrepreneurship. As of June 2025, over 5.67 million candidates have been trained.

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY): Targets rural youth unemployment through demand-driven, placement-linked skill training.

- Skill India Digital Hub (SIDH): A unified digital platform integrating skilling, education, employment, and entrepreneurship, enabling Aadhaar-based tracking and performance-linked payments.

- Global Mobility: Efforts to equip Indian workers with globally recognized certifications and facilitate their employment overseas through Mobility Partnership Agreements (MMPAs) with countries like France, Germany, and Israel.

Challenges and Areas for Improvement

Despite significant achievements, the Skill India Mission continues to face several challenges:

- Quality of Training: Variability in training quality across institutes, shortage of qualified trainers, and outdated curricula remain concerns, leading to diluted training effectiveness.

- Skill-Industry Mismatch: Training programs sometimes fail to align with the rapidly evolving industry needs, particularly in emerging technologies, due to limited industry collaboration and poor forecasting. Placement rates, while improving, still need to be higher in some components (e.g., ~42.8% for PMKVY STT till PMKVY 3.0).

- Infrastructure and Accessibility: Inadequate training facilities, digital tools, and connectivity, especially in rural and remote areas, limit outreach and equitable access to quality skilling.

- Retention and Wages: Issues like brain drain of skilled workers, low wages in certain sectors, and limited upskilling opportunities can affect the retention of skilled personnel.

- Digital Divide: The push for digital skilling is challenged by the existing digital divide, particularly in rural areas, hindering access to online learning resources.

- Fragmented Implementation: While efforts have been made to unify the ecosystem, some overlapping schemes and governance structures can still lead to coordination challenges.

- Awareness and Mobilization: Ensuring that all eligible individuals, particularly from marginalized communities, are aware of and can access skilling opportunities remains a key area.

Future Outlook and Way Forward

As India moves towards its vision of a ‘Viksit Bharat by 2047’, the Skill India Mission is poised for further evolution:

- New National Skill Development and Entrepreneurship Policy: This upcoming policy is expected to be a game-changer, redefining skilling, upskilling, and reskilling to prepare the workforce for a dynamic global economy.

- Focus on Emerging Technologies: Continued emphasis on skills for Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, green energy, and Industry 4.0 technologies. The launch of a dedicated AI skilling program for schoolchildren under ‘Bharat SkillNxt 2025’ is a testament to this.

- Demand-Driven Skilling: Strengthening linkages between industry and academia to ensure curriculum relevance and practical exposure through enhanced apprenticeships and work-based learning.

- Digital Transformation: Leveraging the Skill India Digital Hub (SIDH) for integrated access to training, digital certification, AI-based career mapping, and placements.

- Public-Private-People-Panchayat (4Ps) Partnership: Promoting localized skilling delivery through synergy among industry, community, and grassroots governance.

- Inclusivity and Regional Equity: Special focus on increasing the participation of women, differently-abled individuals, and those from underserved regions like the North East.

- Outcome-Based Monitoring: Strengthening Aadhaar-linked verification, digital certification, and placement tracking for greater transparency and accountability.

The 10-year journey of the Skill India Mission has been transformative, empowering millions and laying a strong foundation for a skilled workforce. The challenges, though significant, are being addressed with renewed policy focus and strategic interventions. The success of the Mission is critical for India to fully leverage its demographic dividend and achieve its aspirations of becoming a global economic powerhouse.

India’s Strategic Push for Global Capability Centers (GCCs): From Cost Centers to Innovation Hubs

Syllabus: GS3/ Indian Economy (Employment, Skilling); Infrastructure; Growth & Development; GS2/ Government Policies & Interventions

In Context

India is strategically accelerating its efforts to become the undisputed global hub for Global Capability Centers (GCCs). The Union government, recognizing the immense potential of GCCs to drive high-value services, skill development, and economic growth, is implementing comprehensive policy interventions. This proactive push is positioning India as a critical partner for multinational corporations seeking not just cost efficiencies but also innovation, digital transformation, and strategic value creation.

What are Global Capability Centers (GCCs)?

Global Capability Centers (GCCs), often referred to as Global In-house Centers (GICs) or captive centers, are wholly-owned subsidiaries or offshore units established by multinational corporations (MNCs) in foreign countries (like India) to manage a wide range of business functions.

Historically, GCCs primarily focused on cost arbitrage and handled back-office operations, IT support, and basic business process outsourcing (BPO) functions. However, their role has significantly evolved:

- From Cost Centers to Strategic Hubs: Today’s GCCs are strategic powerhouses, acting as critical extensions of the parent company. They are involved in high-value functions such as:

- Software Development and Product Engineering

- Data Analytics and Data Science

- Cybersecurity and Cloud Computing

- Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Emerging Technologies

- Research and Development (R&D)

- Financial Planning & Analysis (FP&A)

- Human Resources, Procurement, and Supply Chain Management

- Customer Experience Management (CX)

- Key Distinction from Outsourcing: Unlike traditional outsourcing, where services are provided by third-party vendors, GCCs are captive centers. This means MNCs retain full ownership and control over processes, intellectual property (IP), and quality standards, ensuring deeper integration and alignment with corporate goals.

Why GCCs Matter for India: The Strategic Advantage

India has emerged as the leading destination for GCCs globally, currently hosting over 1,800 GCCs (as of March 2024), employing nearly 2 million professionals, and contributing significantly to the country’s export revenue (estimated at $64.6 billion in FY 2024). This growth is driven by several compelling advantages:

- Deep and Diverse Talent Pool:

- India produces over 1.5 million engineering graduates annually, with a growing number of professionals skilled in cutting-edge technologies like AI, data science, and robotics.

- This vast, English-speaking, and adaptable workforce provides an unparalleled advantage in terms of both quantity and quality of talent.

- Cost-Effectiveness and Scalability:

- While moving beyond just cost savings, India still offers significant operational cost advantages (30-50% lower compared to Western markets).

- The vast scale of India’s talent market and developing infrastructure allows for rapid scalability of operations, enabling companies to quickly expand their teams as needed.

- Maturing Ecosystem and Digital Infrastructure:

- With over 30 years of experience in hosting GCCs, India offers a mature, well-established ecosystem.

- Robust digital public infrastructure (like Aadhaar, UPI), high-speed internet, and a thriving startup culture provide a strong foundation for secure and scalable digital operations.

- Innovation and R&D Hub:

- Indian GCCs are increasingly becoming centers of excellence for product development, advanced analytics, and strategic R&D, contributing to global innovation agendas.

- Collaboration with India’s vibrant startup ecosystem and academic institutions further fuels this innovation.

- Time-Zone Advantage:

- India’s strategic time zone allows for seamless 24/7 operations, enabling round-the-clock service delivery to global customers.

- Government Policy Support:

- The Indian government is actively promoting GCC growth through supportive policies, simplified FDI norms, tax benefits, and skill development initiatives.

- National frameworks (like the one announced in the 2025-26 Budget) and state-specific GCC policies (e.g., Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh) aim to streamline processes and encourage expansion into Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities.

Strategic Push by the Government: Key Interventions

The Indian government is making a concerted push to consolidate India’s position as a premier GCC destination:

- National Framework: A national framework to guide GCC expansion, with a focus on emerging technologies like AI, engineering R&D, and digital transformation, was a key announcement in the 2025-26 Union Budget.

- Ease of Doing Business: Efforts are being made to reduce approval timelines, enhance tax certainty (including Advance Pricing Agreements), and integrate administrative support across various ministries.

- Tier-2 and Tier-3 City Promotion: The government is actively encouraging investment and expansion into Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities (e.g., Coimbatore, Jaipur, Chandigarh, Vadodara, Kochi) to decentralize growth, tap into new talent pools, and offer lower operational costs.

- Skill Development and Industry-Academia Linkages:

- Government initiatives like the PM Internship Scheme and Mutual Recognition of Skills and Standards are aligning workforce capabilities with GCC needs.

- Emphasis on industry-academia partnerships, Centers of Excellence (CoEs), and internship programs to create a future-ready talent pipeline.

- Global Outreach: Targeted efforts to attract non-US multinationals from countries like Germany, Japan, and Nordic nations to diversify India’s GCC portfolio.

- GIFT City (Gujarat International Finance Tec-City): Showcased as a model for regulatory facilitation, GIFT City offers a conducive environment for financial and tech GCCs.

Future Outlook and Challenges

The outlook for GCCs in India is highly optimistic. Projections suggest that the number of GCCs in India could grow to 2,200-2,500 by 2030, contributing up to $105-110 billion to the economy and employing 2.8 to 4.5 million professionals.

However, challenges remain:

- Talent War and Upskilling: Intense competition for top-tier talent, coupled with the need for continuous upskilling to keep pace with rapidly evolving technologies (AI, ML, blockchain).

- Hybrid Work Models: Effectively managing and optimizing hybrid work models to ensure collaboration, productivity, and employee engagement.

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy: Ensuring robust cybersecurity and data governance frameworks to handle sensitive global data.

- Infrastructure Development: Sustained investment in digital and physical infrastructure, especially in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, to support continued growth.

- Evolving Operating Models: GCCs need to constantly evolve their operating models to move further up the value chain and avoid becoming mere execution centers.

India’s strategic push for GCCs is a testament to its ambition to become a global knowledge economy and a hub for advanced technological innovation. By fostering a supportive ecosystem and focusing on talent development, infrastructure, and policy certainty, India is poised to solidify its position as the preferred destination for MNCs seeking strategic value from their global operations.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS): A Key Indicator of India’s Employment Landscape

Syllabus: GS3/ Indian Economy (Employment, Growth, Development); GS1/ Indian Society (Demography, Social Issues)

In Context

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) is a crucial survey conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), Government of India, to provide high-frequency estimates of key employment and unemployment indicators in India. Recently, the June 2025 monthly bulletin of the PLFS was released, offering the latest insights into India’s labour market trends, highlighting an overall unemployment rate of 5.6% and indicating some shifts in urban and rural employment dynamics.

What is the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)?

The PLFS was launched in April 2017 with a primary objective to generate reliable and timely estimates of various labour force indicators. Before PLFS, India relied on quinquennial (five-yearly) Employment-Unemployment Surveys by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). The PLFS aimed to address the need for more frequent data to capture the dynamic nature of the labour market.

Key Objectives of PLFS:

- Quarterly Estimates for Urban Areas: To estimate key employment and unemployment indicators (Labour Force Participation Rate, Worker Population Ratio, Unemployment Rate) in the short time interval of three months for urban areas using the ‘Current Weekly Status’ (CWS) approach.

- Annual Estimates for Rural and Urban Areas: To estimate employment and unemployment indicators in both ‘Usual Status’ (Principal and Subsidiary Status – ps+ss) and ‘Current Weekly Status’ (CWS) for both rural and urban areas annually.

- Monthly Estimates (from Jan 2025): The methodology has been revamped from January 2025 to also provide monthly estimates for rural and urban areas in CWS at the all-India level, enabling even more timely policy interventions.

Key Indicators Measured by PLFS:

The PLFS provides data on several crucial labour market indicators:

- Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR): It is the percentage of persons in the labour force (i.e., persons who are working or seeking or available for work) in the population.

- Worker Population Ratio (WPR): It is defined as the percentage of employed persons in the population.

- Unemployment Rate (UR): It is defined as the percentage of persons unemployed among the persons in the labour force.

Concepts of Activity Status:

The PLFS captures activity status based on two different reference periods:

- Usual Status (ps+ss): This status is determined based on the activities pursued by a person during the last 365 days preceding the date of survey. It identifies the “usual principal activity status” (the activity on which a person spent relatively more time) and “subsidiary economic activity status” (any additional economic activity performed for 30 days or more during the year). This gives a long-term view of employment.

- Current Weekly Status (CWS): This status is determined based on the activities pursued by a person during the last 7 days preceding the date of survey. A person is considered unemployed under CWS if they did not work for at least one hour during the week but actively sought or were available for work. This provides a more real-time snapshot of the labour market.

Methodology and Data Collection:

- Sampling Design: The PLFS employs a rotational panel sampling design.

- Urban Areas: In urban areas, each selected household is visited four times. The initial visit uses a ‘First Visit Schedule,’ followed by three periodic ‘Revisit Schedules.’ This ensures that 75% of the First-Stage Sampling Units (FSUs) are matched between two consecutive visits.

- Rural Areas: Until recently, rural samples did not have revisits in the same manner. However, with the revamped design from January 2025, a rotational panel sampling design has been adopted for both rural and urban areas, where each selected household is visited four times in four consecutive months.

- Data Collection: Data is collected on a voluntary basis from household members of the selected households. The survey covers both rural and urban areas of India, with a few exceptions (e.g., inaccessible areas, certain institutional populations).

- Revamped PLFS (from January 2025): The new design aims to:

- Provide monthly estimates of key labour market indicators (LFPR, WPR, UR) for both rural and urban areas at the all-India level using the CWS approach.

- Extend the coverage of quarterly estimates to rural areas, thereby producing quarterly estimates for the entire country (both rural and urban) in CWS.

- Shift the annual report cycle to the calendar year (January-December).

- Enhanced sample size for improved representativeness and precision.

- District as the primary geographical unit (basic stratum) for selecting FSUs to ensure sample observations from most districts.

Recent Key Findings (June 2025 Monthly Bulletin – 15 years and above age group):

The latest PLFS data for June 2025 provides important insights:

- Unemployment Rate (UR):

- Overall Unemployment Rate (UR) remained steady at 5.6% in June, similar to May.

- Urban UR increased to 7.1% in June from 6.9% in May.

- Rural UR decreased to 4.9% in June from 5.1% in May.

- Youth (15-29 age group) joblessness saw a marginal increase to 15.3% in June from 15% in May. For young women, this rate rose sharply to 17.4% from 16.3% in May in the same age group.

- Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR):

- Overall LFPR for persons aged 15 years and above slightly dipped to 54.2% in June from 54.8% in May.

- Rural LFPR stood at 56.1%, while urban LFPR was lower at 50.4%.

- Female LFPR for rural areas was 35.2%, and for urban areas it was 25.2%.

- Worker Population Ratio (WPR):

- Overall WPR fell to 51.2% in June from 51.7% in May.

- Rural WPR was 53.3%, while urban WPR was 46.8%.

- Overall female WPR was 30.2%.

Key Trends and Implications:

- Urban-Rural Divergence: The data indicates a widening urban-rural divide in unemployment trends, with urban areas showing an increase in joblessness while rural areas experience a slight decline. This could be influenced by seasonal agricultural patterns and a shift towards informal, self-initiated activities (own-account work) in rural areas.

- Youth Joblessness: The persistent high unemployment rate among youth, especially young women in urban areas, remains a significant concern, highlighting challenges in matching skills with available jobs and generating adequate formal employment opportunities.

- Seasonal Factors: The report attributes marginal dips in LFPR and WPR to intense summer heat and agricultural seasonality, along with a shift of some unpaid rural helpers (particularly women) towards domestic duties.

- Informalisation of Work: The rise in own-account work, particularly in rural areas, can reflect a lack of formal job opportunities, pushing individuals into less secure, informal employment.

Significance of PLFS:

- Evidence-Based Policymaking: PLFS provides critical, high-frequency data for policymakers to understand the dynamics of the Indian labour market and formulate targeted interventions for job creation, skill development, and social security.

- Monitoring Economic Trends: The indicators help in monitoring the health of the economy, assessing the impact of various economic policies on employment and unemployment.

- Demographic Dividend: Understanding labour force trends is essential for India to effectively harness its demographic dividend by ensuring its large working-age population is gainfully employed.

- Transparency and Accountability: Regular and transparent release of PLFS data enhances accountability of government initiatives and allows for public scrutiny of labour market performance.

The PLFS, especially with its revamped methodology providing monthly estimates, is an invaluable tool for understanding India’s complex and evolving employment landscape, crucial for addressing the nation’s socio-economic challenges and ensuring inclusive growth.

STPI Aims to Spread IT Sector Growth Nationwide: Driving Inclusive Digital Transformation

Syllabus: GS3/ Indian Economy (IT Sector, Growth, Development, Employment); GS2/ Government Policies & Interventions (Digital India, Startup India)

In Context

The Software Technology Parks of India (STPI), an autonomous society under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), is aggressively repositioning itself to spearhead the next wave of inclusive and innovation-driven IT growth across the country. With a strategic focus on expanding beyond traditional metro cities, STPI aims to decentralize IT sector development, empower local talent and entrepreneurs, and foster a robust software product-based digital economy, aligning with the vision of a ‘Viksit Bharat’.

Role of STPI in India’s IT Journey

Established in 1991, STPI played a pivotal role in the initial boom of India’s IT sector. Its original mandate was to:

- Promote Software Exports: Facilitate the development and export of software and IT-enabled services (ITeS).

- Provide Statutory Services: Offer essential services like software certification, tax holidays, and other incentives to export-oriented units.

- Establish Infrastructure: Provide high-speed data communication facilities, incubation centers, and other common amenities.

Over the past three decades, STPI has been instrumental in transforming India into a global IT powerhouse. STPI-registered units alone contributed software exports worth over ₹10.59 lakh crore (about $110 billion) in FY 2024–25, accounting for over half of India’s total software exports, which exceeded $200 billion.

The New Mandate: STPI 2.0 – Inclusive Growth and Product Nation

STPI is now embarking on its “2.0” growth phase, with a broader and more inclusive mandate:

- Wider Geographical Outreach to Tier-2 & Tier-3 Cities:

- STPI has significantly expanded its footprint from just three initial centers to 67 centers across the country.

- Crucially, 59 of these centers are now located in Tier-II and Tier-III cities (e.g., Coimbatore, Bhubaneswar, Lucknow, Chandigarh, Mysuru, Hubballi, Kochi, Imphal, Shillong), reflecting a conscious effort to spread IT growth to previously underrepresented regions.

- The aim is to bring IT-enabled services (ITeS), software development, and business process management (BPM) opportunities closer to smaller towns and cities.

- Creation of Large-Scale Incubation Infrastructure:

- To support emerging startups and tech ventures in these smaller cities, STPI has developed over 17 lakh square feet of incubation space.

- These “plug-and-play” incubation facilities provide ready-to-work office spaces, reliable network connectivity, access to labs, mentorship, and marketing support, lowering the barriers to entry for new entrepreneurs and MSMEs.

- Fostering a Product-Based Digital Economy:

- While India has excelled in IT services exports, STPI recognizes the need to pivot towards a robust software product-based economy for higher value addition and long-term competitiveness.

- This aligns with the National Policy on Software Products (NPSP) 2019, which emphasizes indigenous innovation and Intellectual Property (IP)-led growth.

- STPI is actively working to transform India into a “product nation” by encouraging the design and development of innovative software products and solutions.

- Promoting Entrepreneurship and Start-up Culture:

- STPI has established 24 Centres of Entrepreneurship (CoEs) nationwide, each focusing on specific emerging technology domains like AI, IoT, Blockchain, FinTech, MedTech, AR/VR, Gaming, Animation, and ACES (Automated, Connected, Electric, & Shared) Mobility.

- Through initiatives like the Next Generation Incubation Scheme (NGIS), STPI provides comprehensive support to startups, including seed/risk funding (up to ₹25 lakh for promising startups), mentoring, workshops, and investor interfaces.

- In the last three years, STPI has supported around 1,500 startups, leading to the creation of approximately 800 Intellectual Properties (IPRs) and over 2,000 product innovations. These firms have collectively raised over ₹600 crore in funding.

- Targeting Youth and Local Talent:

- By expanding into Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities and establishing incubation centers closer to educational institutions, STPI aims to empower youth and aspiring entrepreneurs from these regions.

- This provides a quick start for engineering graduates from smaller towns, reducing the need to migrate to metro cities for opportunities.

- Digital Infrastructure and Ecosystem Support:

- STPI is expanding digital infrastructure to remote and underserved areas, aligned with the Digital India program.

- It also provides specialized services like vulnerability assessment and penetration testing for government and industry, and has launched “Ananta,” a proposed hyperscale cloud made by Indians for Indians.

- The SAYUJ startup network helps connect entrepreneurs with mentors and investors.

Impact and Way Forward

STPI’s renewed focus on inclusive growth is crucial for India’s digital future:

- Balanced Regional Development: It will help in decongesting major IT hubs and ensure that the benefits of the IT sector are distributed more equitably across the country.

- Job Creation: Decentralization is expected to lead to significant job creation in smaller towns, benefiting local economies and reducing rural-urban migration.

- Deepening Innovation: By fostering a vibrant startup ecosystem in diverse locations, STPI is catalyzing grassroots innovation and IP creation, moving India up the technology value chain.

- Harnessing Untapped Potential: It allows for tapping into a larger, diverse talent pool that may not have access to opportunities in major cities.

However, for this vision to be fully realized, continuous efforts are needed in:

- Quality of Education and Skilling: Ensuring that educational institutions in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities provide industry-relevant skills.

- Policy Support from States: Active collaboration and supportive policies from state governments are vital for creating a conducive environment.

- Funding and Investment: Attracting sufficient venture capital and angel investment to support startups in emerging clusters.

- Digital Connectivity: Further strengthening high-speed internet connectivity in remote areas.

By acting as a catalyst for IT growth beyond metro cities, STPI is not just expanding India’s technological footprint but also working towards a more inclusive, equitable, and innovation-driven digital economy, aligning with the long-term vision of a ‘Viksit Bharat’.

Confined Field Trials on GM Maize: A Contentious Move in India

Syllabus: GS3/Science and Technology (Biotechnology, GM Crops); Environment (Conservation, Bio-safety); Agriculture (Crop Management, Food Security)

In Context

The Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC), India’s apex regulatory body for genetically modified (GM) organisms under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC), has recently given its approval for confined field trials of two types of genetically modified (GM) maize in India. These trials are expected to commence in the ongoing Kharif (summer) season at the Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) in Ludhiana, Punjab. This decision has ignited a fresh round of debate and strong objections from environmental activists and farmers’ organizations.

Understanding Confined Field Trials (CFTs)

Confined Field Trials (CFTs) are a crucial stage in the evaluation of GM crops before any consideration for commercial release. They are conducted under strict biosafety conditions to:

- Assess Agronomic Performance: Evaluate how the GM crop performs in a real-world agricultural environment, including yield, growth characteristics, and response to various climatic conditions.

- Evaluate Beneficial Traits: Test the efficacy of the introduced genetic traits, such as:

- Herbicide Tolerance (HT): In the case of GM maize, this involves assessing its ability to withstand the application of specific herbicides (like glyphosate) that would otherwise kill conventional maize. The objective is to study weed control efficacy.

- Insect Resistance (Bt): This involves evaluating the effectiveness of the incorporated Bt gene (from Bacillus thuringiensis bacteria) in providing resistance against target lepidopteran pests (e.g., stem borers) and reducing pesticide use.

- Ensure Environmental Biosafety: Monitor potential impacts on non-target organisms, biodiversity, soil health, and assess the risk of gene flow to conventional or wild relatives. Strict measures are employed to achieve reproductive isolation (e.g., buffer zones, staggered planting, physical barriers) and prevent the spread of GM material.

- Generate Data for Regulatory Approval: Collect scientific data that is essential for regulatory authorities (like GEAC and Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation – RCGM) to make informed decisions regarding environmental release and potential commercialization.

CFTs are a step between laboratory/greenhouse research (contained conditions) and full environmental release. They are typically conducted over several seasons to gather comprehensive data.

The GM Maize in Question and the Regulatory Process

The two types of GM maize approved for trials in Punjab have been developed by Bayer Crop Science Limited (formerly Monsanto). They possess stacked traits, meaning they are engineered for both:

- Herbicide Tolerance (HT): Specifically designed to tolerate glyphosate, a broad-spectrum herbicide.

- Insect Resistance (Bt): Engineered to produce proteins that are toxic to certain insect pests.

The approval process for GM crops in India is multi-layered and governed by the “Rules for the Manufacture, Use, Import, Export and Storage of Hazardous Microorganisms, Genetically Engineered Organisms or Cells, 1989” notified under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. The key regulatory bodies involved are:

- Institutional Biosafety Committees (IBSCs): At the institutional level, for initial assessment.

- Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation (RCGM) under DBT: For overseeing contained research and recommending biosafety research level (BRL) trials.

- Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC) under MoEF&CC: The apex body responsible for approving large-scale confined field trials and environmental release of GM crops. It evaluates biosafety data and makes recommendations for commercial release.

Controversies and Objections

The decision to permit GM maize trials has been met with significant opposition from various quarters:

- Glyphosate Ban in Punjab: A major point of contention is that Punjab had banned the sale and use of glyphosate in 2018 due to concerns about its potential negative impacts on human health (linked to carcinogenic effects) and soil ecosystems. Activists question the rationale of conducting trials for a herbicide-tolerant maize designed to withstand a chemical that is already prohibited in the state.

- Health and Environmental Concerns:

- Health Risks: Opponents cite studies linking glyphosate to health issues like non-Hodgkin lymphoma and express concerns about potential allergens or long-term health effects of consuming GM maize.

- Biodiversity Risks: Worries about potential gene flow to native maize varieties or wild relatives, which could lead to “superweeds” (herbicide-resistant weeds) or affect non-target organisms (beneficial insects).

- Increased Chemical Dependence: Concerns that HT GM crops could lead to an increased reliance on herbicides like glyphosate, potentially exacerbating environmental and health problems.

- Pest Resistance: Lessons from Bt cotton, where initial success was followed by pest resistance (e.g., pink bollworm developing resistance to earlier Bt versions), raise fears of similar outcomes with GM maize, leading to a need for more toxic alternatives.

- Lack of Transparency and Public Consultation: Critics, particularly from the ‘Coalition for a GM-Free India’ and farmer’s bodies like Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS), allege a lack of transparency in the approval process, demanding public consultation, independent review, and parliamentary oversight. They argue that NOCs are being issued without adequate scientific basis being revealed to the public.

- Track Record of Compliance: Allegations have been made regarding PAU’s past compliance during confined field trials of HT mustard, citing photographic evidence of violations where safety protocols were reportedly breached without action.

- Food vs. Feed Concerns: BKS has highlighted that in countries like the US, a large percentage of GM maize is used for animal feed or industrial purposes, whereas in India, a significant portion is for human consumption. This raises concerns about the possibility of adulteration and unapproved GM maize entering the human food chain at various stages.

PAU’s Defense and the Government’s Stance

- Research Mandate: PAU officials, including Vice-Chancellor Satbir Singh Gosal, have clarified that the university’s role is strictly limited to conducting scientific research and field trials under the guidelines of the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) and established standard operating procedures. They emphasize that PAU has no involvement in decisions related to the commercialization of the crop.

- Data-Driven Decisions: PAU argues that scientific assessments, including risks and benefits, cannot be made without robust field data generated from such trials. They stress the importance of independent, university-led research to inform policy decisions.

- Controlled Environment: The trials are asserted to be highly controlled and confined, with strict regulations to prevent gene flow and environmental exposure.

- Necessity for Future Challenges: The Punjab Agriculture Minister, Gurmeet Singh Khudian, supported the trials, stating the necessity to develop new crop varieties to face future challenges, especially given maize’s lower water consumption compared to crops like cotton.

Broader Context of GM Crops in India

- Bt Cotton: Currently, Bt cotton is the only GM crop approved for commercial cultivation in India (since 2002). It accounts for over 90% of India’s cotton acreage. While it initially led to significant production increases and reduced pesticide use, concerns about pest resistance and declining yields in recent years persist.

- Other GM Crops: Bt brinjal was approved by GEAC in 2009 but placed under an indefinite moratorium. GM Mustard (DMH-11) received environmental clearance in 2022 but its commercial release is on hold pending Supreme Court and regulatory approvals due to ongoing legal challenges and public opposition. GM variants of chickpea, pigeonpea, and sugarcane are also in various stages of research and trials.

- Illegal Cultivation: There have been reports of illegal cultivation of unapproved GM crops, including Herbicide Tolerant (HT) Bt cotton and even some GM maize varieties, raising concerns about regulatory loopholes and biosafety.

Way Forward

The ongoing debate surrounding GM maize trials highlights the need for:

- Robust and Transparent Regulatory Framework: Ensuring that the GEAC operates with utmost transparency, engaging diverse stakeholders, and clearly communicating the scientific basis for its decisions.

- Independent Biosafety Research: Funding and promoting independent, long-term biosafety studies to address public health and environmental concerns.

- Effective Monitoring and Compliance: Strengthening mechanisms for rigorous monitoring of confined field trials to prevent any breaches of biosafety protocols.

- Public Dialogue and Education: Fostering informed public discourse based on scientific evidence, addressing misconceptions, and building trust in the regulatory process.

- Comprehensive Risk-Benefit Analysis: Beyond immediate yield benefits, a holistic assessment of the socio-economic, environmental, and health impacts of GM crops in the long run.

The confined field trials of GM maize in Punjab represent a critical step in India’s ongoing journey with genetically modified crops, balancing the promise of increased agricultural productivity with genuine concerns about environmental and health safety.

Miscellaneous

Thiru K. Kamaraj

Syllabus: GS1/History

In News

- The Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid homage to Thiru K. Kamaraj Ji on his birth anniversary.

Thiru K. Kamaraj

- Kumaraswami Kamaraj was born in Tamil Nadu on July 15, 1903.

- His early life was shaped by the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and meeting Mahatma Gandhi, which inspired him to join the freedom movement.

- He became active in the Indian National Congress, participating in non-cooperation and Salt Satyagraha movements.

- He was elected unopposed to the Madras Legislative Assembly in 1937 and re-elected in 1946.

- That same year, he was also elected to the Constituent Assembly of India and later to Parliament in 1952.

Other Political roles

- Kamaraj became the Chief Minister of Madras in 1954.

- In 1963, he proposed to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru that senior Congress leaders should resign from ministerial posts to focus on strengthening the party organisation.

- This initiative became known as the ‘Kamaraj Plan.’

- In recognition of his service to the nation, he was posthumously awarded Bharat Ratna in 1976.

Legacy

- He was at the forefront of India’s freedom struggle and provided invaluable leadership in the formative years of our journey after Independence.

- His noble ideals and emphasis on social justice inspire us all greatly.

Spinning of Earth

Syllabus: GS1/Geography

In News

- Earth is expected to spin slightly faster on July 9, July 22, and August 5, 2025, shortening each day by 1.3 to 1.51 milliseconds.

Spinning of Earth

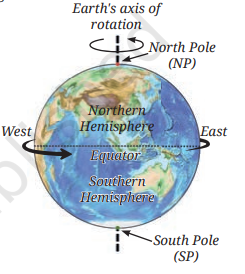

- Earth spins on an imaginary axis passing through the North Pole, its center of mass, and the South Pole.

- The earth rotates on its axis from west to east completing a rotation in 23 hours and 56 minutes.

- This axis shifts naturally due to changing mass distribution inside and on the planet — a phenomenon called polar motion.

- Historically, Earth’s rotation has slowed over billions of years due to the moon moving away, lengthening our days.

- However, recent years have shown variability, with 2020 seeing the fastest rotations since the 1970s and the shortest recorded day on July 5, 2024.

- Factors like mantle circulation, ocean currents, and hurricanes contribute to this shift, which can vary by several meters each year.

- Human activities, particularly climate change, also influence polar motion.

- Studies in 2016 and 2021 found that melting glaciers and ice in Greenland and related water mass redistribution have accelerated the axis drift since the 1990s.

Impacts

- Although days may vary by milliseconds, our clocks remain unchanged, since only a 900-millisecond difference would require adjusting time zones.

- These differences are tracked by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), which adds “leap seconds” when needed.

Source :IE

Furlough & Parole

Syllabus: GS2/Polity and Governance

Context

- The Delhi High Court ruled that prison authorities can decide on parole or furlough requests of convicts whose appeals are pending in the Supreme Court.

About

- In India, parole and furlough are two forms of temporary release granted to prisoners under specific circumstances.

- Parole is generally granted by the Divisional Commissioner, while furlough is granted by the Deputy Inspector General of Prisons.

Parole

- Parole is a conditional release granted to a prisoner for a specific purpose or emergency for a short duration. It is not a right, but a privilege granted under defined conditions.

- It is granted to maintain social relations with family and the community in order to fulfil familial and social obligations and responsibilities.

- The prisoner has to spend extra time in prison for the period spent by him outside the Jail on parole.

- Parole may be of the following two types: Emergency Parole and Regular Parole.

- Legal Framework: Governed by State Prison Rules (as prison is a State subject under the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution).

Furlough in India

- Furlough means release of a prisoner for a short period of time after a gap of a certain qualified number of years of incarceration by way of motivation for him maintaining good conduct and remain disciplined in the prison.

- This is purely an incentive for good conduct in the prison.

- Therefore the period spent by the prisoner outside the prison on furlough shall be counted towards his sentence.

- Legal Basis: Also governed by State Prison Rules, and varies slightly between states.

- Under trial prisoners are not eligible for regular parole and furlough, and may be released only on emergency parole, that too by the order of the concerned trial court.

Source: IE

Indian Council of Agricultural Research

Syllabus: GS2/ Governance, GS3/ Agriculture

Context

- The 97th foundation of Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) organised was observed recently.

About ICAR

- It is an autonomous body under the Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE), Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India.

- ICAR is the apex body for coordinating, guiding, and managing research and education in agriculture and allied sectors in India.

- Established in 1929, it was earlier known as the Imperial Council of Agricultural Research.

- It is headquartered at NASC Complex, New Delhi.

Major Initiatives in 2024–25

- Global Centre of Excellence on Millets (Shree Anna): Promoting millets globally in line with the International Year of Millets 2023 legacy.

- Genome Editing in 40 Crops: Enhancing climate resilience, pest resistance, and nutritional value.

- Clean Plant Programme: Operational in 9 centres to ensure disease-free planting material.

- MAHARISHI (Millets and Other Ancient Grains International Research Initiative): Preserving traditional grains.

- All India Network Project on Biotech Crops and Emerging Pests: Strengthening research against climate-induced pest outbreaks.

Source: PIB

Statathon: A Data Journey Towards Viksit Bharat

Syllabus: GS2/ Governance

Context

- The National Statistical Office (NSO), in collaboration with the Ministry of Education’s Innovation Cell, has launched a national-level grand challenge titled “Statathon – A Data Journey Towards Viksit Bharat.”

About

- The Statathon is designed to harness emerging technologies and innovative solutions to transform the landscape of official statistics in India.

- Organised under the aegis of MoSPI’s Data Innovation Lab (DI Lab) initiative, the Statathon marks an important milestone in the commemoration of 75 years of the National Sample Survey (NSS).

- The challenge invites participation to address five problem statements, each covering different phases of the data lifecycle; collection, processing & analysis, and dissemination.

What are the Problem Statements?

- API Gateway for Survey Datasets: Development of a scalable, configurable, and privacy-compliant API gateway enabling SQL-based data retrieval from NSS datasets.

- AI-Powered Smart Survey Tool: Creation of an AI-enabled, multilingual, mobile-friendly survey application using digital platforms for real-time data collection.

- AI-Enhanced Application for Automated Data Processing: Development of AI based configurable modules for data scrutiny, statistical analysis, and report generation.

- Semantic Search for Occupation Classification (NCO): Implementation of a semantic search interface using NLP and Gen AI for intuitive, context-aware searches across occupational codes.

- Evaluation and Enhancement of Data Anonymisation Practices: Review of current anonymisation methods and development of a robust safe data tool to ensure data privacy and security.

India’s first Digital Nomad Village inaugurated in Sikkim

Syllabus: GS3/ Economy, Infrastructure

Context

- The country’s first Digital Nomad Village was officially inaugurated at Yakten village, Pakyong district in Sikkim.

About the Nomad Sikkim Initiative

- Objective: To develop Yakten as a sustainable remote work hub for digital professionals while supporting local tourism and rural livelihoods.

- Facilities:

- Village-wide high-speed Wi-Fi connectivity through two dedicated internet lines.

- Provision of inverters to ensure uninterrupted power.

- Plans under Jal Jeevan Mission to address water scarcity.

- Model: Enables professionals to work remotely in a peaceful, eco-friendly setting, providing a year-round alternative to seasonal tourism.